Monday, April 10, 2006

Friday, April 07, 2006

Pre-existent Ideas

Doesn’t the notion that God has foreseen all that will transpire suggest that all ideas that occur to us, or to God, are already preexistent? Have all ideas that have ever been thought existed from eternity? Or was there a time when God wasn’t aware of them?

Oy, that makes my head hurt!

Oy, that makes my head hurt!

Friday, March 17, 2006

03/14/2006—

I want to know why I doubt. I want to know what I doubt. How do I thoroughly analyze my doubts and beliefs, and why I doubt and why I believe? Where do I start? Perhaps I should start with the Resurrection. Did it happen? If I say yes, then where’s my evidence? Did he appear to his apostles? Did he appear to the women? To the men on the road to Emmaus? Are the documents which record it reliable? Does it prove Jesus to be God? If so, what kind of God is he? Is that even a pertinent question? How about the other resurrections Jesus performed? If they’re true resurrections, doesn’t that make his own more likely?

But why do I doubt? Are the doubts emotional or intellectual? Or is my problem the unwillingness to believe, consciously or unconsciously? Or does the answer lie in some of all three?

I want to know why I doubt. I want to know what I doubt. How do I thoroughly analyze my doubts and beliefs, and why I doubt and why I believe? Where do I start? Perhaps I should start with the Resurrection. Did it happen? If I say yes, then where’s my evidence? Did he appear to his apostles? Did he appear to the women? To the men on the road to Emmaus? Are the documents which record it reliable? Does it prove Jesus to be God? If so, what kind of God is he? Is that even a pertinent question? How about the other resurrections Jesus performed? If they’re true resurrections, doesn’t that make his own more likely?

But why do I doubt? Are the doubts emotional or intellectual? Or is my problem the unwillingness to believe, consciously or unconsciously? Or does the answer lie in some of all three?

Friday, March 10, 2006

03/10/2006—

Greg Koukl made some comments a while back on the evolution/creation matter. He thought it likely that pain and animal death did exist before the fall because he saw pain as being good, though we may not like it. He also thought God would’ve had to have created the natural deadly weapons of animals by the time the creation was finished, because after God called the finished creation good, and stopped creating.

My response is this, that God may have, as other creationists have suggested, preprogrammed into our genes during the creation the possible weapons and instincts to maintain nature’s balance after the fall, anticipating our fall. I mean, if these weapons and instincts hadn’t existed after the fall, then maybe God’s creation would’ve experienced wholesale chaos. Animals attacking other animals and their own environments—for no apparent reason except to cause pain and destruction. There’d be no balance in nature. So God gives us instincts and weapons to establish a balance—we attack animals for constructive reasons, to eat. We destroy trees to build houses and make paper.

When old-earthers ask young-earthers how there could’ve been 24-hr. days and morning and evenings before the sun, moon, and stars were created, the young-earther response is that God created a light—I was going to say he created light, but Genesis doesn’t say what’s it’s extent. It could’ve surrounded the earth. But now I’m remebering that God divided the darkness from the light. But there was a point when there was only the light. So what was it? Why was it there before the sun? He calls the light “day,” and the darkness “night.” It seems apparent that he’s referring to a literal 24-hr. day. And why mention morning and evening if the days weren’t literal? Those seem to be very concrete details. Why didn’t Moses just say “one day passed?” I don’t really know the answers.

If pain is a bad thing, then why did God design us with a nervous system that delivers painful sensations whenever we’re injured? See 02/20/2006.

Can God take a thing that is inherently bad and use it for good?

Greg Koukl made some comments a while back on the evolution/creation matter. He thought it likely that pain and animal death did exist before the fall because he saw pain as being good, though we may not like it. He also thought God would’ve had to have created the natural deadly weapons of animals by the time the creation was finished, because after God called the finished creation good, and stopped creating.

My response is this, that God may have, as other creationists have suggested, preprogrammed into our genes during the creation the possible weapons and instincts to maintain nature’s balance after the fall, anticipating our fall. I mean, if these weapons and instincts hadn’t existed after the fall, then maybe God’s creation would’ve experienced wholesale chaos. Animals attacking other animals and their own environments—for no apparent reason except to cause pain and destruction. There’d be no balance in nature. So God gives us instincts and weapons to establish a balance—we attack animals for constructive reasons, to eat. We destroy trees to build houses and make paper.

When old-earthers ask young-earthers how there could’ve been 24-hr. days and morning and evenings before the sun, moon, and stars were created, the young-earther response is that God created a light—I was going to say he created light, but Genesis doesn’t say what’s it’s extent. It could’ve surrounded the earth. But now I’m remebering that God divided the darkness from the light. But there was a point when there was only the light. So what was it? Why was it there before the sun? He calls the light “day,” and the darkness “night.” It seems apparent that he’s referring to a literal 24-hr. day. And why mention morning and evening if the days weren’t literal? Those seem to be very concrete details. Why didn’t Moses just say “one day passed?” I don’t really know the answers.

If pain is a bad thing, then why did God design us with a nervous system that delivers painful sensations whenever we’re injured? See 02/20/2006.

Can God take a thing that is inherently bad and use it for good?

Tuesday, March 07, 2006

Tuesday, February 21, 2006

02/12/2006—

Here’s an idea:

Many scientists will accept an infinite, natural “foundation” for the universe, whether that’s infinite space in which our finite universe exists, infinite sheets of energy that create universes whenever they bump together, or a “quantum foam” in which our universe is one of a infinite number of universes. But, what about information? Isn’t this even more basic? The above “foundations” need information to exist, for without information, there would be chaos. Information implies a designer who uses it to bring order.

Another weird, but related idea on information is about the word “idea.” Are ideas infinite in duration? Do they exist before we think of them? For instance, say one day I meet somebody, and after a few days I forget I ever met them. Does that then mean that never met them? Of course not. But a few days before I met them, I was not aware that I would ever meet them. Does that mean I didn’t? Or just that I’m not aware of that yet?

Let’s go back to “idea.” Actions arise first from ideas. If one day I built a table, and the previous day I hadn’t thought of it, does that mean the idea never existed prior to my thinking about it? (See, I told you this is weird.)

Need to think about this some more.

02/20/2006—

Greg Koukl of Stand To Reason made some comments a while back on the evolution/creation matter. He thought it likely that pain and animal death did exist before the fall because he saw pain as being good, though we may not like it. He also thought God would’ve had to have created the natural deadly weapons of animals by the time the creation was finished, because after God called the finished creation good, and stopped creating.

My response is this, that God may have, as other creationists have suggested, preprogrammed into our genes during the creation the possible weapons and instincts to maintain nature’s balance after the fall, anticipating our fall. I mean, if these weapons and instincts hadn’t existed after the fall, then maybe God’s creation would’ve experienced wholesale chaos. Animals attacking other animals and their own environments—for no apparent reason except to cause pain and destruction. There’d be no balance in nature. So God gives us instincts and weapons to establish a balance—we attack animals for constructive reasons, to eat. We attack trees to build houses.

02/21/2006—

When old-earthers ask young-earthers how there could’ve been 24-hr. days and morning and evenings before the sun, moon, and stars were created, the young-earther response is that God created a light—I was going to say he created light, but Genesis doesn’t say what’s it’s extent. It could’ve surrounded the earth. But now I’m remebering that God divided the darkness from the light. But there was a point when there was only the light. So what was it? Why was it there before the sun? He calls the light “day,” and the darkness “night.” It seems apparent that he’s referring to a literal 24-hr. day. And why mention morning and evening if the days weren’t literal? Those seem to be very concrete details. Why didn’t Moses just say “one day passed?” I don’t really know the answers.

Here’s an idea:

Many scientists will accept an infinite, natural “foundation” for the universe, whether that’s infinite space in which our finite universe exists, infinite sheets of energy that create universes whenever they bump together, or a “quantum foam” in which our universe is one of a infinite number of universes. But, what about information? Isn’t this even more basic? The above “foundations” need information to exist, for without information, there would be chaos. Information implies a designer who uses it to bring order.

Another weird, but related idea on information is about the word “idea.” Are ideas infinite in duration? Do they exist before we think of them? For instance, say one day I meet somebody, and after a few days I forget I ever met them. Does that then mean that never met them? Of course not. But a few days before I met them, I was not aware that I would ever meet them. Does that mean I didn’t? Or just that I’m not aware of that yet?

Let’s go back to “idea.” Actions arise first from ideas. If one day I built a table, and the previous day I hadn’t thought of it, does that mean the idea never existed prior to my thinking about it? (See, I told you this is weird.)

Need to think about this some more.

02/20/2006—

Greg Koukl of Stand To Reason made some comments a while back on the evolution/creation matter. He thought it likely that pain and animal death did exist before the fall because he saw pain as being good, though we may not like it. He also thought God would’ve had to have created the natural deadly weapons of animals by the time the creation was finished, because after God called the finished creation good, and stopped creating.

My response is this, that God may have, as other creationists have suggested, preprogrammed into our genes during the creation the possible weapons and instincts to maintain nature’s balance after the fall, anticipating our fall. I mean, if these weapons and instincts hadn’t existed after the fall, then maybe God’s creation would’ve experienced wholesale chaos. Animals attacking other animals and their own environments—for no apparent reason except to cause pain and destruction. There’d be no balance in nature. So God gives us instincts and weapons to establish a balance—we attack animals for constructive reasons, to eat. We attack trees to build houses.

02/21/2006—

When old-earthers ask young-earthers how there could’ve been 24-hr. days and morning and evenings before the sun, moon, and stars were created, the young-earther response is that God created a light—I was going to say he created light, but Genesis doesn’t say what’s it’s extent. It could’ve surrounded the earth. But now I’m remebering that God divided the darkness from the light. But there was a point when there was only the light. So what was it? Why was it there before the sun? He calls the light “day,” and the darkness “night.” It seems apparent that he’s referring to a literal 24-hr. day. And why mention morning and evening if the days weren’t literal? Those seem to be very concrete details. Why didn’t Moses just say “one day passed?” I don’t really know the answers.

Tuesday, January 24, 2006

The essay below was written a few weeks back as a response to an opinion article that I read in the city's weekly alternative newspaper. An edited version was published was published there. The full essay is below.

I was interested to read Joshua Welch’s article on morality and religion and I’d like to make some comments on it.

If a guide to living is written (or, as the theologians put it, verbally-inspired) by the person who designed every single thing in universe and knows the location and speed of every single subatomic particle in the universe, then yes, I’d say he knows a heck of a lot more about living rightly than we do and that it may well be valid to live by that guide. If that Person is the infinitely perfect Christian God, than it is totally correct to do so.

I agree with him religious bigotry has fueled a great deal of hatred and violence throughout history. But, frankly, until this last century, atheism just hasn’t had its chance. In the 20th century, Josef Stalin was responsible for the deaths of tens of millions and Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia killed 2 million Cambodians, one-quarter of the population. And let’s not forget Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, where at least two students, Cassie Bernall and Rachel Scott, were murdered for believing in God. My point is not that atheism leads to more violence then religion, but that people are such that they can be directed to violence by any set of beliefs.

And an additional point is this: that atheism is also a religion. I quote from the Encarta ® World English Dictionary ©, one definition for a religion is, “Personal beliefs or values: a set of strongly-held beliefs, values, and attitudes that somebody lives by.” That sounds very much like Mr. Welch. His religion is a set of beliefs about reality and what is right.

He quotes a prominent atheist as saying that, “‘Our ethics must be firmly planted in the soil of scientific self-knowledge. They must be improvable and adaptable.’” According to the scientific method, nothing even as certain as the “fact” of the theory of relativity is ever completely, 100% certain. It can be proved correct in a hundred different tests, but if another theory proves explains the evidence even better, out it goes. And since ethics is supposed to be established in this, there is no firm footing for ethics.

But this defies logic. If ethics must be improved and adapted, what must they be improved and adapted from? Why, they have to be adapted and improved from a prior standard of ethics. And that standard was adapted and improved from a prior standard. And so on, and so forth back into the mists of time. If that were true, that would imply an infinite number of regressions into time or “improvements.” There has to be a time before which there were no other improvements.

Then, he makes an appeal to common sense. Whose common sense, his or mine? Not everyone shares the same common sense. He says morality should be about things like compassion and ending suffering. But why? Why are they good? What’s his standard of behavior? What if it’s different than mine? Why are certain behaviors wrong and others right?

Mr. Welch is correct in saying that our morality must be based on rationality, not emotionalism. But when morality is based on what one wants to do, rather than on an absolute standard established by the one who knows all and has created all, that seems rather seems foolish at best.

I was interested to read Joshua Welch’s article on morality and religion and I’d like to make some comments on it.

If a guide to living is written (or, as the theologians put it, verbally-inspired) by the person who designed every single thing in universe and knows the location and speed of every single subatomic particle in the universe, then yes, I’d say he knows a heck of a lot more about living rightly than we do and that it may well be valid to live by that guide. If that Person is the infinitely perfect Christian God, than it is totally correct to do so.

I agree with him religious bigotry has fueled a great deal of hatred and violence throughout history. But, frankly, until this last century, atheism just hasn’t had its chance. In the 20th century, Josef Stalin was responsible for the deaths of tens of millions and Pol Pot and the Khmer Rouge in Cambodia killed 2 million Cambodians, one-quarter of the population. And let’s not forget Columbine High School in Littleton, Colorado, where at least two students, Cassie Bernall and Rachel Scott, were murdered for believing in God. My point is not that atheism leads to more violence then religion, but that people are such that they can be directed to violence by any set of beliefs.

And an additional point is this: that atheism is also a religion. I quote from the Encarta ® World English Dictionary ©, one definition for a religion is, “Personal beliefs or values: a set of strongly-held beliefs, values, and attitudes that somebody lives by.” That sounds very much like Mr. Welch. His religion is a set of beliefs about reality and what is right.

He quotes a prominent atheist as saying that, “‘Our ethics must be firmly planted in the soil of scientific self-knowledge. They must be improvable and adaptable.’” According to the scientific method, nothing even as certain as the “fact” of the theory of relativity is ever completely, 100% certain. It can be proved correct in a hundred different tests, but if another theory proves explains the evidence even better, out it goes. And since ethics is supposed to be established in this, there is no firm footing for ethics.

But this defies logic. If ethics must be improved and adapted, what must they be improved and adapted from? Why, they have to be adapted and improved from a prior standard of ethics. And that standard was adapted and improved from a prior standard. And so on, and so forth back into the mists of time. If that were true, that would imply an infinite number of regressions into time or “improvements.” There has to be a time before which there were no other improvements.

Then, he makes an appeal to common sense. Whose common sense, his or mine? Not everyone shares the same common sense. He says morality should be about things like compassion and ending suffering. But why? Why are they good? What’s his standard of behavior? What if it’s different than mine? Why are certain behaviors wrong and others right?

Mr. Welch is correct in saying that our morality must be based on rationality, not emotionalism. But when morality is based on what one wants to do, rather than on an absolute standard established by the one who knows all and has created all, that seems rather seems foolish at best.

Saturday, January 14, 2006

12/03/2005—

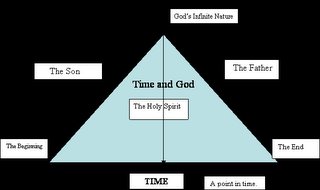

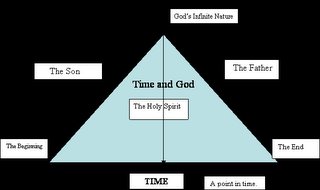

If God knows everything about the future, then he should be able to predict his own actions. But doesn’t that very notion suggest that his actions are predetermined by someone else? If his actions aren’t preset, then wouldn’t he not know the future, thus nullifying his claim to be all-knowing? We know two things about God. That he does know all things about the future and that he is completely sovereign, that is, he’s not limited by any external force, only by his own nature, so his actions aren’t preset. How do we resolve a seeming contradiction? Well, one answer at least, is that God exists outside of time, in a place where past, present, and future have no meaning. An “eternal now,” as it’s called. It’s as if God could see the past, present and future happening all at once. Why wouldn’t this apply to his experience of his creation, as well?

Perhaps it’s because he wants to give us freedom to choose. But, if he had the same relationship to time as he does to eternity, wouldn’t he experience it also as that “eternal now?” Certainly, in my model, the Father and the Son have limited their perspectives on creation, but what is the Holy Spirit’s perspective? Maybe his p.o.v. is each and every moment, not being aware or a past or a future. This seems a very childlike perspective and were there no God, any being with perspective would be quite vulnerable. It seems to me that this would limit the Spirit to acting rather than thinking.

Is there such a thing as the present? I guess the answers is “yes,” because we experience it. Could it be an illusion, constructed by our minds to make sense of the world? The “future” is a “grammar tense referring to things to come: the tense or form of a verb used to refer to events that are going to happen or have not yet happened. Also called future tense.” The “past” means “expressing action that took place previously: used to describe or relating to the verb tense that is used for an action that took place previously . . . time before the present: the time before the present and the events that happened then.”[1] Isn’t the present simply the point at which past and future meet? And yet “future” is something that hasn’t happened and “past” that already has. So, it seems there is a gap, though I can’t see it. And it seems an unbridgeable one.

10:50pm—

How is it that the Son lived among us as 100% man and 100% God? Many have said this suggests he had two natures, one human, one divine. This is a puzzle that is quite the opposite of the one concerning the Trinity. The Trinity is described as one nature, three persons. Jesus can be described as two natures, one person. Jesus as the Son of God is difficult to imagine this way, though I don’t think it’s illogical. An easier way to think of him might be as The Perfect Man. The first image emphasizes his divisions. The second, his unity. What might make it even easier to imagine is to remember that we’re in a process of becoming more and more like him and will become as perfect as he is, if not in this life, then in the next. This suggests we’re experiencing a joining of God’s nature to our own.

If God knows everything about the future, then he should be able to predict his own actions. But doesn’t that very notion suggest that his actions are predetermined by someone else? If his actions aren’t preset, then wouldn’t he not know the future, thus nullifying his claim to be all-knowing? We know two things about God. That he does know all things about the future and that he is completely sovereign, that is, he’s not limited by any external force, only by his own nature, so his actions aren’t preset. How do we resolve a seeming contradiction? Well, one answer at least, is that God exists outside of time, in a place where past, present, and future have no meaning. An “eternal now,” as it’s called. It’s as if God could see the past, present and future happening all at once. Why wouldn’t this apply to his experience of his creation, as well?

Perhaps it’s because he wants to give us freedom to choose. But, if he had the same relationship to time as he does to eternity, wouldn’t he experience it also as that “eternal now?” Certainly, in my model, the Father and the Son have limited their perspectives on creation, but what is the Holy Spirit’s perspective? Maybe his p.o.v. is each and every moment, not being aware or a past or a future. This seems a very childlike perspective and were there no God, any being with perspective would be quite vulnerable. It seems to me that this would limit the Spirit to acting rather than thinking.

Is there such a thing as the present? I guess the answers is “yes,” because we experience it. Could it be an illusion, constructed by our minds to make sense of the world? The “future” is a “grammar tense referring to things to come: the tense or form of a verb used to refer to events that are going to happen or have not yet happened. Also called future tense.” The “past” means “expressing action that took place previously: used to describe or relating to the verb tense that is used for an action that took place previously . . . time before the present: the time before the present and the events that happened then.”[1] Isn’t the present simply the point at which past and future meet? And yet “future” is something that hasn’t happened and “past” that already has. So, it seems there is a gap, though I can’t see it. And it seems an unbridgeable one.

10:50pm—

How is it that the Son lived among us as 100% man and 100% God? Many have said this suggests he had two natures, one human, one divine. This is a puzzle that is quite the opposite of the one concerning the Trinity. The Trinity is described as one nature, three persons. Jesus can be described as two natures, one person. Jesus as the Son of God is difficult to imagine this way, though I don’t think it’s illogical. An easier way to think of him might be as The Perfect Man. The first image emphasizes his divisions. The second, his unity. What might make it even easier to imagine is to remember that we’re in a process of becoming more and more like him and will become as perfect as he is, if not in this life, then in the next. This suggests we’re experiencing a joining of God’s nature to our own.

12/02/2005—

God’s love requires a certain amount of free will to exist. But God’s power requires total control in order to impose his justice upon us.

If God stands at the end of time, looking back on the time that has passed, and knowing how it all works out, and if he stands at the root of time, having planned everything, but not knowing how everything will come out, then it seems we’re stuck with a conundrum. The answer must be where the past and future meet, the present. The present carries within it the uncertain potential of a future not worked our yet, and a past with a certainty of potential realized. But, how can a moment be certain and uncertain at the same time? I dunno, maybe the one is uncertain in one way, and the other certain in another way.

Is it possible that past, future, and possibly present, have a trinitarian structure, which would allow them exist simultaneously? The present cannot exist without the past and future, as if it’s literally a line between the two, and we perceive the line where the two join. Can the future exist without the past? Yes, it does exist. But does the past exist without the future? No. This would suggest a hierarchy: the present depends on the past and future, past depends on the future, and the future depends on nothing. But do the past, present, and future have any reality? The future seems to be all potential. The past seems to be all spent potential. And the present is where we spend it. This is where potential manifests itself into reality, where choices are actually made, and events actually occur. How is it that potential at all points in time and space can be stored and spent at the same time? How is it that with the Father standing at one end of time and the Son at the other, that they can observe all existence happening, yet not happening just yet? This is where our free will lies. The Son, on the one hand, stands at the root of time, having planned how things should go, but not knowing how. This gives us our freedom. But, the Father, who stands at the end of time, knows what did happen, which gives us limits on our freedom. Limits caused by the laws of physics, by human laws, various relationships, natural disasters, etc.

Why does God the Father have to know the future? If he didn’t, or chose not to know it, what would that mean? It would mean that God has withdrawn from his creation. Assuming that my assumption about the Father seeing the future by looking back on the past is true, if God gave up his knowledge of the future he’d be giving up his presence in the present, too. Because, either he exists infinitely or he doesn’t exist at all. He’d be giving up his control and foreknowledge over history. Were that so, the Son could take over for the Father and still design the future. But, it may possible, that Jesus would have to stick to his single role, creating and saving the world. That would lead the universe into eventual chaos. If the Son left, then the universe wouldn’t be here at all.

God’s love requires a certain amount of free will to exist. But God’s power requires total control in order to impose his justice upon us.

If God stands at the end of time, looking back on the time that has passed, and knowing how it all works out, and if he stands at the root of time, having planned everything, but not knowing how everything will come out, then it seems we’re stuck with a conundrum. The answer must be where the past and future meet, the present. The present carries within it the uncertain potential of a future not worked our yet, and a past with a certainty of potential realized. But, how can a moment be certain and uncertain at the same time? I dunno, maybe the one is uncertain in one way, and the other certain in another way.

Is it possible that past, future, and possibly present, have a trinitarian structure, which would allow them exist simultaneously? The present cannot exist without the past and future, as if it’s literally a line between the two, and we perceive the line where the two join. Can the future exist without the past? Yes, it does exist. But does the past exist without the future? No. This would suggest a hierarchy: the present depends on the past and future, past depends on the future, and the future depends on nothing. But do the past, present, and future have any reality? The future seems to be all potential. The past seems to be all spent potential. And the present is where we spend it. This is where potential manifests itself into reality, where choices are actually made, and events actually occur. How is it that potential at all points in time and space can be stored and spent at the same time? How is it that with the Father standing at one end of time and the Son at the other, that they can observe all existence happening, yet not happening just yet? This is where our free will lies. The Son, on the one hand, stands at the root of time, having planned how things should go, but not knowing how. This gives us our freedom. But, the Father, who stands at the end of time, knows what did happen, which gives us limits on our freedom. Limits caused by the laws of physics, by human laws, various relationships, natural disasters, etc.

Why does God the Father have to know the future? If he didn’t, or chose not to know it, what would that mean? It would mean that God has withdrawn from his creation. Assuming that my assumption about the Father seeing the future by looking back on the past is true, if God gave up his knowledge of the future he’d be giving up his presence in the present, too. Because, either he exists infinitely or he doesn’t exist at all. He’d be giving up his control and foreknowledge over history. Were that so, the Son could take over for the Father and still design the future. But, it may possible, that Jesus would have to stick to his single role, creating and saving the world. That would lead the universe into eventual chaos. If the Son left, then the universe wouldn’t be here at all.

12/01/2005—

I can see how trinitarian structure of the Godhead makes it possible for God to have more than one point of view on time. But how can the past and the future exist at the same time if the future is not preset? Could it be that time is infinite, just as God is? Problem there is that time usually comes with change. Does the bible say God is changeless? But didn’t he change in the act of creating the universe.

God cannot have all points of view simultaneously for free will to be so. For him to have our points of view would be for him to be each and everyone of us. This seems to be patently false for I don’t perceive myself to be an omnipotent, omnipresent, and omniscient being.

I can see how trinitarian structure of the Godhead makes it possible for God to have more than one point of view on time. But how can the past and the future exist at the same time if the future is not preset? Could it be that time is infinite, just as God is? Problem there is that time usually comes with change. Does the bible say God is changeless? But didn’t he change in the act of creating the universe.

God cannot have all points of view simultaneously for free will to be so. For him to have our points of view would be for him to be each and everyone of us. This seems to be patently false for I don’t perceive myself to be an omnipotent, omnipresent, and omniscient being.

11/30/2005—

I have a question: if God knows what is going to happen to everything in existence, does he know what will happen to him? Are his actions pre-determined? He is supposed to be completely sovereign. There are no limitations on him, except those dictated by his nature. But, if he’s infinite, then can he change? If he can change, then that may suggest that he can grow, which would suggest he has limits to grow beyond.

Well, there’s two possible answers to my question: yes, he does know what will happen to him, because he is always looking back on his existence, which is infinite, and also looking on whatever present moment he’s in. Another answer is no, because he cannot see what comes after whatever present moment he’s in.

I have a question: if God knows what is going to happen to everything in existence, does he know what will happen to him? Are his actions pre-determined? He is supposed to be completely sovereign. There are no limitations on him, except those dictated by his nature. But, if he’s infinite, then can he change? If he can change, then that may suggest that he can grow, which would suggest he has limits to grow beyond.

Well, there’s two possible answers to my question: yes, he does know what will happen to him, because he is always looking back on his existence, which is infinite, and also looking on whatever present moment he’s in. Another answer is no, because he cannot see what comes after whatever present moment he’s in.

11/29/2005—

What is Christmas all about?

This year, I seem to have a different feeling about Christmas. I want it to mean more. When I was growing up and into adulthood, I spent Christmas with my parents and there just wasn’t really much to it. We might go to church on Christmas Eve (usually without Dad), but more likely we’d go see Christmas lights. Then we’d come home and open presents. But I was always deeply dissatisfied and it was hard to hide it, as my parents know well. Christmas was about presents for me, but now I find myself more actively looking for some satisfaction in Christmas. I will be making an effort to go to a Christmas Eve service, even though I work that evening. In the month before Christmas, I will be buying Christmas movies (with Christian themes) and Christmas music (again, with Christian themes). I’ve purchased one of my favorite movies, It’s A Wonderful Life. And I’ve got my radio tuned to the station that plays Christmas music all the time (see my comments on that above). And I’ve put up a two-foot tall artificial tree in my apartment. But still, I feel like I’m still missing the mark.

I have, though, recently bought a book that might help turn me around. It’s Lee Strobel’s new book, The Case for Christmas. His premise is that “Jesus is the reason for the season,” as they say, and if he didn’t exist, or wasn’t God, or didn’t rise from the dead, then Christmas is meaningless. I’ve also started to read C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia, and that may help, too. And all this thinking I’ve done recently.

I’ll report back later.

What is Christmas all about?

This year, I seem to have a different feeling about Christmas. I want it to mean more. When I was growing up and into adulthood, I spent Christmas with my parents and there just wasn’t really much to it. We might go to church on Christmas Eve (usually without Dad), but more likely we’d go see Christmas lights. Then we’d come home and open presents. But I was always deeply dissatisfied and it was hard to hide it, as my parents know well. Christmas was about presents for me, but now I find myself more actively looking for some satisfaction in Christmas. I will be making an effort to go to a Christmas Eve service, even though I work that evening. In the month before Christmas, I will be buying Christmas movies (with Christian themes) and Christmas music (again, with Christian themes). I’ve purchased one of my favorite movies, It’s A Wonderful Life. And I’ve got my radio tuned to the station that plays Christmas music all the time (see my comments on that above). And I’ve put up a two-foot tall artificial tree in my apartment. But still, I feel like I’m still missing the mark.

I have, though, recently bought a book that might help turn me around. It’s Lee Strobel’s new book, The Case for Christmas. His premise is that “Jesus is the reason for the season,” as they say, and if he didn’t exist, or wasn’t God, or didn’t rise from the dead, then Christmas is meaningless. I’ve also started to read C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia, and that may help, too. And all this thinking I’ve done recently.

I’ll report back later.

11/29/05—

In my opinion, time by definition, is always in motion, for anything in time must be in a process of change. Therefore, if God were a single being and if he were entirely in time only, he would be constantly changing. So, he couldn’t know the future, because that implies the future is set, not changeable. On the other hand, if there were three persons within the one God, they could assume three different points of view. The Father would know the future—no, scratch that. The Father would have to be outside of time in order to know the past and he wouldn’t need to know the future because he’s outside of it. The Son would originally have lived outside of time, then created it, held it together, and thereby began to experience time and change, and therefore a lack of knowledge of the future. His lack of foreknowledge implies his subservient role in relation to the Father, though he is equal in his nature and power.

So what does all this have to do with our free will? It’s clear that free will is possible. After all, the Son and the Spirit both have free wills apart from the Father. And it’s their infinite nature that provides them that freedom. We, on the other hand, prior to our salvation, were slaves to sin, and we would be utterly depraved were it not for God’s influence in the world. Our free will, then, is based entirely on God’s intervention into the world. That may be an argument against predestination. After all, he could’ve just granted free will to those he chose to be saved. Wait. If he chose them, would they have any choice? Before I tackle predestination, perhaps I ought to work on settling the issue of determinism. I think that it’s been established that God can know what we consider the future by looking back at it as the past. But does time have to have ended and passed by him completely in order for him to look at it all? It would seem so.

It’s the Godhead’s infinite nature that allows the Father to know all, yet with the Son acting freely (and the Holy Spirit, too). Yet, at the same time, that same infinite nature allows the Father to know what the Son will do (and the Holy Spirit, too.) Remember that an infinite line cannot be divided, which makes the second proposition true. Also, remember that there can be more that one infinite line existing simultaneously within one main line, even though, paradoxically, the main line cannot be split. This makes the first proposition true. In other words, this paradox of multiple infinities in one infinity makes possible how God can foreknow and not foreknow the future.

In my opinion, time by definition, is always in motion, for anything in time must be in a process of change. Therefore, if God were a single being and if he were entirely in time only, he would be constantly changing. So, he couldn’t know the future, because that implies the future is set, not changeable. On the other hand, if there were three persons within the one God, they could assume three different points of view. The Father would know the future—no, scratch that. The Father would have to be outside of time in order to know the past and he wouldn’t need to know the future because he’s outside of it. The Son would originally have lived outside of time, then created it, held it together, and thereby began to experience time and change, and therefore a lack of knowledge of the future. His lack of foreknowledge implies his subservient role in relation to the Father, though he is equal in his nature and power.

So what does all this have to do with our free will? It’s clear that free will is possible. After all, the Son and the Spirit both have free wills apart from the Father. And it’s their infinite nature that provides them that freedom. We, on the other hand, prior to our salvation, were slaves to sin, and we would be utterly depraved were it not for God’s influence in the world. Our free will, then, is based entirely on God’s intervention into the world. That may be an argument against predestination. After all, he could’ve just granted free will to those he chose to be saved. Wait. If he chose them, would they have any choice? Before I tackle predestination, perhaps I ought to work on settling the issue of determinism. I think that it’s been established that God can know what we consider the future by looking back at it as the past. But does time have to have ended and passed by him completely in order for him to look at it all? It would seem so.

It’s the Godhead’s infinite nature that allows the Father to know all, yet with the Son acting freely (and the Holy Spirit, too). Yet, at the same time, that same infinite nature allows the Father to know what the Son will do (and the Holy Spirit, too.) Remember that an infinite line cannot be divided, which makes the second proposition true. Also, remember that there can be more that one infinite line existing simultaneously within one main line, even though, paradoxically, the main line cannot be split. This makes the first proposition true. In other words, this paradox of multiple infinities in one infinity makes possible how God can foreknow and not foreknow the future.

11/26/2005—

More thoughts on free will and predestination:

If God is infinite, he has existed into the infinite past and will exist into the infinite future. Does he exist in time? He may, but I don’t think he has to. Does he have to exist outside time in order to see the beginning from the end? No, but God and time would have to be co-eternal. Here, he’d see every moment as the present or the past, never the future.

But doesn’t setting a limit on what God can and cannot see turn God into a finite being, even though the limitation may not mean much. Here, perhaps, is another example of “trinitarian” structure.

If God is strictly in time and not outside or beyond it, then time must be infinite, with no beginning or end, because God has no beginning or end. From every specific moment in time, he would have perfect knowledge of the past and present, but does not know from that point in time what the future holds. He can base his intentions for the future on his knowledge of the present.

Maybe the three different perspectives are analogous, even a model, of the Trinity’s function in time. Maybe the Father is the one looks back to the past, thereby knowing the future beyond any given moment. Then the Son would be the one who looks forward to the future, who plans it and creates the world in which things will happen, but doesn’t have total control (or doesn’t exercise it) over the creation. He creates change, but is himself unchanged. Then, there’s the Spirit, possibly in the weakest position of all, the present, where all he can do is choose to change in response to stimuli from the past, basing his choice on guesswork about the future.

More thoughts on free will and predestination:

If God is infinite, he has existed into the infinite past and will exist into the infinite future. Does he exist in time? He may, but I don’t think he has to. Does he have to exist outside time in order to see the beginning from the end? No, but God and time would have to be co-eternal. Here, he’d see every moment as the present or the past, never the future.

But doesn’t setting a limit on what God can and cannot see turn God into a finite being, even though the limitation may not mean much. Here, perhaps, is another example of “trinitarian” structure.

If God is strictly in time and not outside or beyond it, then time must be infinite, with no beginning or end, because God has no beginning or end. From every specific moment in time, he would have perfect knowledge of the past and present, but does not know from that point in time what the future holds. He can base his intentions for the future on his knowledge of the present.

Maybe the three different perspectives are analogous, even a model, of the Trinity’s function in time. Maybe the Father is the one looks back to the past, thereby knowing the future beyond any given moment. Then the Son would be the one who looks forward to the future, who plans it and creates the world in which things will happen, but doesn’t have total control (or doesn’t exercise it) over the creation. He creates change, but is himself unchanged. Then, there’s the Spirit, possibly in the weakest position of all, the present, where all he can do is choose to change in response to stimuli from the past, basing his choice on guesswork about the future.

11/26/2005—

I’m listening to Christmas music on the radio right now. It’s kinda depressing. One, so much it is repetitive. They’re all singing the same songs. Two, so many of the songs have no substance. They often don’t deal with what Christmas is all about, Jesus’ birth. That’s just sad. I’m not sure whether there are just so many Christmas songs that aren’t really about Christmas, or if the singers just aren’t choosing to sing those kinds of songs.

How can my life right now better reflect the meaning of Christmas? I think it’s always been about presents for me and it should be about more than that. But, Christmas with my Mom and Dad—well, maybe it hasn’t been about presents, but I don’t think it has been about much else either. Nothing that sets it apart. In the last several years, the ‘tradition’ we’ve done more consistently than any other, besides opening presents late Christmas Eve, is driving around to see Christmas lights. I do enjoy that, with my parents’ selection of music playing in the car CD player, but where’s the meaning in it that isn’t in other holidays, or in other days, even?

I shall give all this some more thought.

Adieu.

I’m listening to Christmas music on the radio right now. It’s kinda depressing. One, so much it is repetitive. They’re all singing the same songs. Two, so many of the songs have no substance. They often don’t deal with what Christmas is all about, Jesus’ birth. That’s just sad. I’m not sure whether there are just so many Christmas songs that aren’t really about Christmas, or if the singers just aren’t choosing to sing those kinds of songs.

How can my life right now better reflect the meaning of Christmas? I think it’s always been about presents for me and it should be about more than that. But, Christmas with my Mom and Dad—well, maybe it hasn’t been about presents, but I don’t think it has been about much else either. Nothing that sets it apart. In the last several years, the ‘tradition’ we’ve done more consistently than any other, besides opening presents late Christmas Eve, is driving around to see Christmas lights. I do enjoy that, with my parents’ selection of music playing in the car CD player, but where’s the meaning in it that isn’t in other holidays, or in other days, even?

I shall give all this some more thought.

Adieu.

11/26/05—

‘Notes on ‘Eternal Security, Cheap Grace, & Free Will’ (STR)’:

What do some Christians find offensive? The concept of ‘once saved always saved’—they feel it takes away a human’s freedom of choice.

Why does it take away choice? Because once we join God, we cannot choose to leave, no how badly we sin or backslide. We’re ‘puppets on a string.’

What is another issue that is often mentioned? Many feel that eternal security for backsliders cheapens God’s grace.

Where is our position in regards to free will? How free are we? Anyone who commits sin is a slave to it. It’s like a dying man who does not have the freedom to be well.

Whose choice is security based on? God’s.

What is salvation based on? It‘s based on God starting and completing the process of salvation. What part do we play? The reception of God’s invitation.

Neither God’s capacity for choice, nor ours is limited by eternal salvation. If he’s offended, he can forgive because he’s the one offended.

How badly must we sin or backslide to lose our salvation? First, refer to what Paul says about forgiveness and salvation in Romans.

How does it say we’re saved? Well, it says that we’re not saved by works. On the contrary, we’re damned by works, as no one can do one’s works perfectly.

How then are we saved? By God’s grace.

How much sin can God forgive? There’s only one that he can’t forgive, one that one is not likely to make if one is saved. All others he can forgive, even crimes committed by the likes Jeffrey Dahmer.

Can God choose not to forgive? No. He told us he would.

If Jeffrey Dahmer can be forgiven, then what does that say about us? That certainly our lesser sins can also be forgived?

How is it that we’re able to choose God? Because he enables us to.

What is our salvation based on? Not works, but on his faithfulness.

‘Notes on ‘Eternal Security, Cheap Grace, & Free Will’ (STR)’:

What do some Christians find offensive? The concept of ‘once saved always saved’—they feel it takes away a human’s freedom of choice.

Why does it take away choice? Because once we join God, we cannot choose to leave, no how badly we sin or backslide. We’re ‘puppets on a string.’

What is another issue that is often mentioned? Many feel that eternal security for backsliders cheapens God’s grace.

Where is our position in regards to free will? How free are we? Anyone who commits sin is a slave to it. It’s like a dying man who does not have the freedom to be well.

Whose choice is security based on? God’s.

What is salvation based on? It‘s based on God starting and completing the process of salvation. What part do we play? The reception of God’s invitation.

Neither God’s capacity for choice, nor ours is limited by eternal salvation. If he’s offended, he can forgive because he’s the one offended.

How badly must we sin or backslide to lose our salvation? First, refer to what Paul says about forgiveness and salvation in Romans.

How does it say we’re saved? Well, it says that we’re not saved by works. On the contrary, we’re damned by works, as no one can do one’s works perfectly.

How then are we saved? By God’s grace.

How much sin can God forgive? There’s only one that he can’t forgive, one that one is not likely to make if one is saved. All others he can forgive, even crimes committed by the likes Jeffrey Dahmer.

Can God choose not to forgive? No. He told us he would.

If Jeffrey Dahmer can be forgiven, then what does that say about us? That certainly our lesser sins can also be forgived?

How is it that we’re able to choose God? Because he enables us to.

What is our salvation based on? Not works, but on his faithfulness.

12/04/2005—

I’ve been giving some thought to the problem of evil. How can a perfect, all-powerful God create, or allow, evil suffering?

It’s his power that allows him to be perfect, for by being infinitely powerful, he is also all-knowing, and so would know himself perfectly; and being infinitely powerful, he could sustain indefinitely his own perfection. Prior to the Fall, God completely supported the entirety of creation. That is, his creation, as he designed it in it’s original perfection, had to be supported by a certain amount, maybe an endless amount, of energy. As part of the Curse, he withdrew some of his original presence.

How was it that Satan, then the demons, then Adam and Eve chose sin? What is the nature of good? If only God existed, would evil exist? If so, does this mean evil exists apart from God? Can one find an answer to the problem of evil that will give solace to someone in a time of suffering?

Like cold being the absence of heat, isn’t evil the absence of good? If good and evil both existed as forces, like two sides in a battle, then you could claim at the least that evil existed alongside God since before the beginning. But, if you see it as the absence of something, than it becomes easier to resolve with the notion of a perfect, all-powerful God. Before the beginning, God probably was all there was (perhaps there were other creations of his, too). I don’t know if he has infinite physical dimensions. Probably does. But one way or the other, there’s no room for anything else.

So, it makes sense to say that Satan didn’t acquire evil. Rather, he pushed out what was good. But, what gave him that very first impetus to dwell on himself for the briefest of additional seconds, rather than focus entirely on God? First, let’s remember that Lucifer and the other angels who followed him were limited creations, infinitely perfect, infinitely powerful beings. They didn’t know all, they couldn’t do all. That may have led some to making assumptions about themselves and God that were irrational, illogical, or unreasonable.

The same thing might have happened to Adam and Eve.

I’ve been giving some thought to the problem of evil. How can a perfect, all-powerful God create, or allow, evil suffering?

It’s his power that allows him to be perfect, for by being infinitely powerful, he is also all-knowing, and so would know himself perfectly; and being infinitely powerful, he could sustain indefinitely his own perfection. Prior to the Fall, God completely supported the entirety of creation. That is, his creation, as he designed it in it’s original perfection, had to be supported by a certain amount, maybe an endless amount, of energy. As part of the Curse, he withdrew some of his original presence.

How was it that Satan, then the demons, then Adam and Eve chose sin? What is the nature of good? If only God existed, would evil exist? If so, does this mean evil exists apart from God? Can one find an answer to the problem of evil that will give solace to someone in a time of suffering?

Like cold being the absence of heat, isn’t evil the absence of good? If good and evil both existed as forces, like two sides in a battle, then you could claim at the least that evil existed alongside God since before the beginning. But, if you see it as the absence of something, than it becomes easier to resolve with the notion of a perfect, all-powerful God. Before the beginning, God probably was all there was (perhaps there were other creations of his, too). I don’t know if he has infinite physical dimensions. Probably does. But one way or the other, there’s no room for anything else.

So, it makes sense to say that Satan didn’t acquire evil. Rather, he pushed out what was good. But, what gave him that very first impetus to dwell on himself for the briefest of additional seconds, rather than focus entirely on God? First, let’s remember that Lucifer and the other angels who followed him were limited creations, infinitely perfect, infinitely powerful beings. They didn’t know all, they couldn’t do all. That may have led some to making assumptions about themselves and God that were irrational, illogical, or unreasonable.

The same thing might have happened to Adam and Eve.

12/05/2005—

So, how is it that God can remove some of his presence from his creation when it is his presence that maintains it?

Could good just be defined as the absence of a substance called evil? If that were so, then God as conceived, all-knowing and all-powerful, could not exist. Why? God, in the Judeo-Christian sense, is defined as absolutely good. If evil exists as a real substance, then either he allowed it or he just couldn’t stop it, which would mean that he is a finite being just as we are, certainly one who doesn’t have all the answers and one who couldn’t absolutely be depended upon in all circumstances. What would be worse is that he created it. Worst of all, he may have created evil, making him not just a God who is cool and indifferent to us, but one who is cruel and barbarous beyond the worst tyrants humanity ever has or ever will produce.

But, what if evil were defined as the absence of a substance called good? If that were so, then God as conceived, all-knowing and all-powerful,would necessarily exist. Why? Because God, in the Judeo-Christian sense, is defined as absolutely good. As in “no hint of evil.” If good exists as a real substance, then he is it. What is better, is that his intentions toward us will always be good. Best of all, all goodness stems from him and never stops. But, if this is true, then doesn’t this undermine the notion of God’s existence? After all, evil things happen.

[1] Encarta ® World English Dictionary © & (P) 1998-2004 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

So, how is it that God can remove some of his presence from his creation when it is his presence that maintains it?

Could good just be defined as the absence of a substance called evil? If that were so, then God as conceived, all-knowing and all-powerful, could not exist. Why? God, in the Judeo-Christian sense, is defined as absolutely good. If evil exists as a real substance, then either he allowed it or he just couldn’t stop it, which would mean that he is a finite being just as we are, certainly one who doesn’t have all the answers and one who couldn’t absolutely be depended upon in all circumstances. What would be worse is that he created it. Worst of all, he may have created evil, making him not just a God who is cool and indifferent to us, but one who is cruel and barbarous beyond the worst tyrants humanity ever has or ever will produce.

But, what if evil were defined as the absence of a substance called good? If that were so, then God as conceived, all-knowing and all-powerful,would necessarily exist. Why? Because God, in the Judeo-Christian sense, is defined as absolutely good. As in “no hint of evil.” If good exists as a real substance, then he is it. What is better, is that his intentions toward us will always be good. Best of all, all goodness stems from him and never stops. But, if this is true, then doesn’t this undermine the notion of God’s existence? After all, evil things happen.

[1] Encarta ® World English Dictionary © & (P) 1998-2004 Microsoft Corporation. All rights reserved.

11/26/2005—

I’m listening to Christmas music on the radio right now. It’s kinda depressing. One, so much it is repetitive. They’re all singing the same songs. Two, so many of the songs have no substance. They often don’t deal with what Christmas is all about, Jesus’ birth. That’s just sad. I’m not sure whether there are just so many Christmas songs that aren’t really about Christmas, or if the singers just aren’t choosing to sing those kinds of songs.

How can my life right now better reflect the meaning of Christmas? I think it’s always been about presents for me and it should be about more than that. But, Christmas with my Mom and Dad—well, maybe it hasn’t been about presents, but I don’t think it has been about much else either. Nothing that sets it apart. In the last several years, the ‘tradition’ we’ve done more consistently than any other, besides opening presents late Christmas Eve, is driving around to see Christmas lights. I do enjoy that, with my parents’ selection of music playing in the car CD player, but where’s the meaning in it that isn’t in other holidays, or in other days, even?

I shall give all this some more thought.

Adieu.

I’m listening to Christmas music on the radio right now. It’s kinda depressing. One, so much it is repetitive. They’re all singing the same songs. Two, so many of the songs have no substance. They often don’t deal with what Christmas is all about, Jesus’ birth. That’s just sad. I’m not sure whether there are just so many Christmas songs that aren’t really about Christmas, or if the singers just aren’t choosing to sing those kinds of songs.

How can my life right now better reflect the meaning of Christmas? I think it’s always been about presents for me and it should be about more than that. But, Christmas with my Mom and Dad—well, maybe it hasn’t been about presents, but I don’t think it has been about much else either. Nothing that sets it apart. In the last several years, the ‘tradition’ we’ve done more consistently than any other, besides opening presents late Christmas Eve, is driving around to see Christmas lights. I do enjoy that, with my parents’ selection of music playing in the car CD player, but where’s the meaning in it that isn’t in other holidays, or in other days, even?

I shall give all this some more thought.

Adieu.

11/26/2005—

More thoughts on free will and predestination:

If God is infinite, he has existed into the infinite past and will exist into the infinite future. Does he exist in time? He may, but I don’t think he has to. Does he have to exist outside time in order to see the beginning from the end? No, but God and time would have to be co-eternal. Here, he’d see every moment as the present or the past, never the future.

But doesn’t setting a limit on what God can and cannot see turn God into a finite being, even though the limitation may not mean much. Here, perhaps, is another example of “trinitarian” structure.

If God is strictly in time and not outside or beyond it, then time must be infinite, with no beginning or end, because God has no beginning or end. From every specific moment in time, he would have perfect knowledge of the past and present, but does not know from that point in time what the future holds. He can base his intentions for the future on his knowledge of the present.

Maybe the three different perspectives are analogous, even a model, of the Trinity’s function in time. Maybe the Father is the one looks back to the past, thereby knowing the future beyond any given moment. Then the Son would be the one who looks forward to the future, who plans it and creates the world in which things will happen, but doesn’t have total control (or doesn’t exercise it) over the creation. He creates change, but is himself unchanged. Then, there’s the Spirit, possibly in the weakest position of all, the present, where all he can do is choose to change in response to stimuli from the past, basing his choice on guesswork about the future.

More thoughts on free will and predestination:

If God is infinite, he has existed into the infinite past and will exist into the infinite future. Does he exist in time? He may, but I don’t think he has to. Does he have to exist outside time in order to see the beginning from the end? No, but God and time would have to be co-eternal. Here, he’d see every moment as the present or the past, never the future.

But doesn’t setting a limit on what God can and cannot see turn God into a finite being, even though the limitation may not mean much. Here, perhaps, is another example of “trinitarian” structure.

If God is strictly in time and not outside or beyond it, then time must be infinite, with no beginning or end, because God has no beginning or end. From every specific moment in time, he would have perfect knowledge of the past and present, but does not know from that point in time what the future holds. He can base his intentions for the future on his knowledge of the present.

Maybe the three different perspectives are analogous, even a model, of the Trinity’s function in time. Maybe the Father is the one looks back to the past, thereby knowing the future beyond any given moment. Then the Son would be the one who looks forward to the future, who plans it and creates the world in which things will happen, but doesn’t have total control (or doesn’t exercise it) over the creation. He creates change, but is himself unchanged. Then, there’s the Spirit, possibly in the weakest position of all, the present, where all he can do is choose to change in response to stimuli from the past, basing his choice on guesswork about the future.

11/29/05—

In my opinion, time by definition, is always in motion, for anything in time must be in a process of change. Therefore, if God were a single being and if he were entirely in time only, he would be constantly changing. So, he couldn’t know the future, because that implies the future is set, not changeable. On the other hand, if there were three persons within the one God, they could assume three different points of view. The Father would know the future—no, scratch that. The Father would have to be outside of time in order to know the past and he wouldn’t need to know the future because he’s outside of it. The Son would originally have lived outside of time, then created it, held it together, and thereby began to experience time and change, and therefore a lack of knowledge of the future. His lack of foreknowledge implies his subservient role in relation to the Father, though he is equal in his nature and power.

So what does all this have to do with our free will? It’s clear that free will is possible. After all, the Son and the Spirit both have free wills apart from the Father. And it’s their infinite nature that provides them that freedom. We, on the other hand, prior to our salvation, were slaves to sin, and we would be utterly depraved were it not for God’s influence in the world. Our free will, then, is based entirely on God’s intervention into the world. That may be an argument against predestination. After all, he could’ve just granted free will to those he chose to be saved. Wait. If he chose them, would they have any choice? Before I tackle predestination, perhaps I ought to work on settling the issue of determinism. I think that it’s been established that God can know what we consider the future by looking back at it as the past. But does time have to have ended and passed by him completely in order for him to look at it all? It would seem so.

It’s the Godhead’s infinite nature that allows the Father to know all, yet with the Son acting freely (and the Holy Spirit, too). Yet, at the same time, that same infinite nature allows the Father to know what the Son will do (and the Holy Spirit, too.) Remember that an infinite line cannot be divided, which makes the second proposition true. Also, remember that there can be more that one infinite line existing simultaneously within one main line, even though, paradoxically, the main line cannot be split. This makes the first proposition true. In other words, this paradox of multiple infinities in one infinity makes possible how God can foreknow and not foreknow the future.

In my opinion, time by definition, is always in motion, for anything in time must be in a process of change. Therefore, if God were a single being and if he were entirely in time only, he would be constantly changing. So, he couldn’t know the future, because that implies the future is set, not changeable. On the other hand, if there were three persons within the one God, they could assume three different points of view. The Father would know the future—no, scratch that. The Father would have to be outside of time in order to know the past and he wouldn’t need to know the future because he’s outside of it. The Son would originally have lived outside of time, then created it, held it together, and thereby began to experience time and change, and therefore a lack of knowledge of the future. His lack of foreknowledge implies his subservient role in relation to the Father, though he is equal in his nature and power.

So what does all this have to do with our free will? It’s clear that free will is possible. After all, the Son and the Spirit both have free wills apart from the Father. And it’s their infinite nature that provides them that freedom. We, on the other hand, prior to our salvation, were slaves to sin, and we would be utterly depraved were it not for God’s influence in the world. Our free will, then, is based entirely on God’s intervention into the world. That may be an argument against predestination. After all, he could’ve just granted free will to those he chose to be saved. Wait. If he chose them, would they have any choice? Before I tackle predestination, perhaps I ought to work on settling the issue of determinism. I think that it’s been established that God can know what we consider the future by looking back at it as the past. But does time have to have ended and passed by him completely in order for him to look at it all? It would seem so.

It’s the Godhead’s infinite nature that allows the Father to know all, yet with the Son acting freely (and the Holy Spirit, too). Yet, at the same time, that same infinite nature allows the Father to know what the Son will do (and the Holy Spirit, too.) Remember that an infinite line cannot be divided, which makes the second proposition true. Also, remember that there can be more that one infinite line existing simultaneously within one main line, even though, paradoxically, the main line cannot be split. This makes the first proposition true. In other words, this paradox of multiple infinities in one infinity makes possible how God can foreknow and not foreknow the future.

11/29/2005—

What is Christmas all about?

This year, I seem to have a different feeling about Christmas. I want it to mean more. When I was growing up and into adulthood, I spent Christmas with my parents and there just wasn’t really much to it. We might go to church on Christmas Eve (usually without Dad), but more likely we’d go see Christmas lights. Then we’d come home and open presents. But I was always deeply dissatisfied and it was hard to hide it, as my parents know well. Christmas was about presents for me, but now I find myself more actively looking for some satisfaction in Christmas. I will be making an effort to go to a Christmas Eve service, even though I work that evening. In the month before Christmas, I will be buying Christmas movies (with Christian themes) and Christmas music (again, with Christian themes). I’ve purchased one of my favorite movies, It’s A Wonderful Life. And I’ve got my radio tuned to the station that plays Christmas music all the time (see my comments on that above). And I’ve put up a two-foot tall artificial tree in my apartment. But still, I feel like I’m still missing the mark.

I have, though, recently bought a book that might help turn me around. It’s Lee Strobel’s new book, The Case for Christmas. His premise is that “Jesus is the reason for the season,” as they say, and if he didn’t exist, or wasn’t God, or didn’t rise from the dead, then Christmas is meaningless. I’ve also started to read C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia, and that may help, too. And all this thinking I’ve done recently.

I’ll report back later.

What is Christmas all about?

This year, I seem to have a different feeling about Christmas. I want it to mean more. When I was growing up and into adulthood, I spent Christmas with my parents and there just wasn’t really much to it. We might go to church on Christmas Eve (usually without Dad), but more likely we’d go see Christmas lights. Then we’d come home and open presents. But I was always deeply dissatisfied and it was hard to hide it, as my parents know well. Christmas was about presents for me, but now I find myself more actively looking for some satisfaction in Christmas. I will be making an effort to go to a Christmas Eve service, even though I work that evening. In the month before Christmas, I will be buying Christmas movies (with Christian themes) and Christmas music (again, with Christian themes). I’ve purchased one of my favorite movies, It’s A Wonderful Life. And I’ve got my radio tuned to the station that plays Christmas music all the time (see my comments on that above). And I’ve put up a two-foot tall artificial tree in my apartment. But still, I feel like I’m still missing the mark.

I have, though, recently bought a book that might help turn me around. It’s Lee Strobel’s new book, The Case for Christmas. His premise is that “Jesus is the reason for the season,” as they say, and if he didn’t exist, or wasn’t God, or didn’t rise from the dead, then Christmas is meaningless. I’ve also started to read C.S. Lewis’ The Chronicles of Narnia, and that may help, too. And all this thinking I’ve done recently.

I’ll report back later.

11/30/2005—

I have a question: if God knows what is going to happen to everything in existence, does he know what will happen to him? Are his actions pre-determined? He is supposed to be completely sovereign. There are no limitations on him, except those dictated by his nature. But, if he’s infinite, then can he change? If he can change, then that may suggest that he can grow, which would suggest he has limits to grow beyond.

Well, there’s two possible answers to my question: yes, he does know what will happen to him, because he is always looking back on his existence, which is infinite, and also looking on whatever present moment he’s in. Another answer is no, because he cannot see what comes after whatever present moment he’s in.

I have a question: if God knows what is going to happen to everything in existence, does he know what will happen to him? Are his actions pre-determined? He is supposed to be completely sovereign. There are no limitations on him, except those dictated by his nature. But, if he’s infinite, then can he change? If he can change, then that may suggest that he can grow, which would suggest he has limits to grow beyond.

Well, there’s two possible answers to my question: yes, he does know what will happen to him, because he is always looking back on his existence, which is infinite, and also looking on whatever present moment he’s in. Another answer is no, because he cannot see what comes after whatever present moment he’s in.

12/01/2005—

I can see how trinitarian structure of the Godhead makes it possible for God to have more than one point of view on time. But how can the past and the future exist at the same time if the future is not preset? Could it be that time is infinite, just as God is? Problem there is that time usually comes with change. Does the bible say God is changeless? But didn’t he change in the act of creating the universe.

God cannot have all points of view simultaneously for free will to be so. For him to have our points of view would be for him to be each and everyone of us. This seems to be patently false for I don’t perceive myself to be an omnipotent, omnipresent, and omniscient being.

I can see how trinitarian structure of the Godhead makes it possible for God to have more than one point of view on time. But how can the past and the future exist at the same time if the future is not preset? Could it be that time is infinite, just as God is? Problem there is that time usually comes with change. Does the bible say God is changeless? But didn’t he change in the act of creating the universe.

God cannot have all points of view simultaneously for free will to be so. For him to have our points of view would be for him to be each and everyone of us. This seems to be patently false for I don’t perceive myself to be an omnipotent, omnipresent, and omniscient being.

12/02/2005—

God’s love requires a certain amount of free will to exist. But God’s power requires total control in order to impose his justice upon us.

If God stands at the end of time, looking back on the time that has passed, and knowing how it all works out, and if he stands at the root of time, having planned everything, but not knowing how everything will come out, then it seems we’re stuck with a conundrum. The answer must be where the past and future meet, the present. The present carries within it the uncertain potential of a future not worked our yet, and a past with a certainty of potential realized. But, how can a moment be certain and uncertain at the same time? I dunno, maybe the one is uncertain in one way, and the other certain in another way.

Is it possible that past, future, and possibly present, have a trinitarian structure, which would allow them exist simultaneously? The present cannot exist without the past and future, as if it’s literally a line between the two, and we perceive the line where the two join. Can the future exist without the past? Yes, it does exist. But does the past exist without the future? No. This would suggest a hierarchy: the present depends on the past and future, past depends on the future, and the future depends on nothing. But do the past, present, and future have any reality? The future seems to be all potential. The past seems to be all spent potential. And the present is where we spend it. This is where potential manifests itself into reality, where choices are actually made, and events actually occur. How is it that potential at all points in time and space can be stored and spent at the same time? How is it that with the Father standing at one end of time and the Son at the other, that they can observe all existence happening, yet not happening just yet? This is where our free will lies. The Son, on the one hand, stands at the root of time, having planned how things should go, but not knowing how. This gives us our freedom. But, the Father, who stands at the end of time, knows what did happen, which gives us limits on our freedom. Limits caused by the laws of physics, by human laws, various relationships, natural disasters, etc.